Silent fisherman

Pelicans, like brown clad monks

travel single file.

"Gray Beach Day" by Wendy DeWitt

A miracle, clad in monk-brown robes.

The Brown pelican is something of a miracle, a conservation success story. A testament to the power of the Endangered Species Act. Almost extinct in the 1970s, their numbers have rebounded such that they have been de-listed as an endangered species.

A Bit about Pelicans

Brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) are split into two main groups: those that nest on the East and Gulf Coasts of the US and those that nest along the Pacific Coast of North and South America.

Brown pelicans nest in groups, called rookeries, on islands that lack mammalian

predators. Most of the West Coast population lives along the Gulf of California in Mexico. Only about 10% of the Pacific population lives in the US, nesting on off-shore islands in the Southern California Bight. Anacapa and Santa Barbara Islands host the largest rookeries in the Channel Islands.

Nest materials vary from rookery to rookery, but they usually consist of a shallow bowl of sticks and twigs, about 30 inches across and about 10 inches deep. Females lay one egg per day for two to four days. Incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid; chicks hatch in about a month. The young require extensive parental care - they remain in the nest for nearly three months and are often fed even after they are able to fly. They reach sexual maturity between three and five years of age. Adults can live a long time: the average lifespan of a wild Brown pelican is about 28 years.

Nest materials vary from rookery to rookery, but they usually consist of a shallow bowl of sticks and twigs, about 30 inches across and about 10 inches deep. Females lay one egg per day for two to four days. Incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid; chicks hatch in about a month. The young require extensive parental care - they remain in the nest for nearly three months and are often fed even after they are able to fly. They reach sexual maturity between three and five years of age. Adults can live a long time: the average lifespan of a wild Brown pelican is about 28 years.The Troubled History of the Brown Pelican

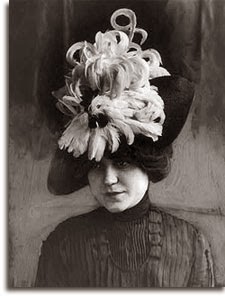

In the early 19th and 20th centuries, hunting for feathers and eggs reduced populations of many bird species, including the Brown pelican. Hunting for brown pelican feathers wasn't as intense as for birds with showier plumes. Egrets, spoonbills, herons, and songbirds were heavily persecuted, often at breeding rookeries, to decorate ladies' hats. The market was highly profitable: at the high point, feathers were worth as much as $2000/ounce in today's dollars!

|

| Lady with a feathered hat. No, that's not a pelican. But you get the idea. (Photo from MD DNR site) |

The trade in bird feathers slowed and stopped by the 1930s. Public awareness of feather hunting made it less socially acceptable to wear feathers. World War I caused a slow-down in international trade for feathers and the economic hardships of the 1930s meant that fewer people had money for such luxuries.

The Migratory Bird Treat Act of 1918 made it illegal to disturb the nest of any native North American species. Since feather hunters and egg collectors concentrated their efforts on breeding rookeries, the Migratory Bird Act significantly reduced mortality of adults and their young.

Fifty years later, in the 1940s, the invention of pesticides like DDT prompted a second crisis for predatory birds like the pelican. Some pesticides, like endrin, killed the birds outright. Breeding colonies in and around Anacapa Island, the largest of the rookeries in the Southern California Bight, reached a low of 76 nesting pairs in 1977, down from the estimated 5000 pairs reported by an egg collector in 1920.

Other pesticides were stored in the bird's fat and interfered with calcium deposition in eggshells. These thin, brittle eggshells broke easily under the weight of the incubating parent, killing the developing chick. The number of young fledging from pelican nests plummeted. The worst year on record for the Anacapa rookeries was 1970, when 552 nests produced only one fledgling chick.

|

| Brown pelicans and cormorants Bird Rock, Catalina Island |

Recently, however, conservation biologists have become concerned about the continued success of Brown pelicans in California... more on this to come!

Sources and Further Reading

All About Birds entry for the Brown pelican, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Scott, V. 2012. "Pelecanus occidentalis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed 9 April 2014.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Species Profile for the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1983. California Brown Pelican Recovery Plan.

The Audubon Society was founded to preserve birds threatened by the plume trade. Interesting articles about this can be found here at Audubon Magazine and here at Lapham's Quarterly.

Photo credits

- All photos except as noted below are from this USFWS page.

- Lady in Feathered Hat -- from the Maryland Department of Natural Resources

- Photo of Brown pelicans and cormorants on Bird Rock was taken by me.

No comments:

Post a Comment